Springfield Daily Leader,

May 21, 1886

Julia knew she was going to die. She had been shot in the chest and left arm and her left thumb was blown apart. But her concern was for her family—” How bad my mother will feel, and my poor sister, how she will miss me.”

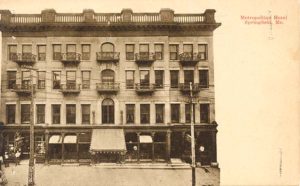

Just a few minutes earlier she sat reading on the front porch of the Morrison house, where she worked as a servant. Deciding that her time was better spent reading the Bible rather than a novel, she went inside to get it. She was walking down the hallway and into the kitchen when she was shot by Theodore Morrison, the son of Nathan Morrison, the first president of what was then Drury College.

That was on May 14. Julia lingered, in considerable pain, for a week. Part of that time she was lucid; sometimes she was delirious. But regardless of her mental state, she was worried about her family.

“She spoke of different members of her family, and…how they would grieve for her, showing very plainly that she believed she would die…I noticed particularly the fact that she was so perfectly willing to die. All that she said on this point showed a beautiful, trusting, Christian character,” stated a witness.

Julia was also worried about Theo. According to the testimony of Frances Fowler, a Drury art teacher who was nearby when the shooting occurred, Julia expressed particular concern that Theo not be blamed. She “seemed to feel keenly that Theo would be severely blamed by his parents, and she felt that it was…an accidental move of Theo’s that caused the gun to go off.”

Julia Patterson died on July 21st. She had been “born of poor but respectable parents, and had recently joined the Christian Church…she and her sister [had] been saving their hard earnings for years in order to assist their parents in purchasing a home, and it almost prostrated them to see her cut down in the bloom of womanhood.”

There was no inquest held in Julia’s death; the coroner was out of town, and in any case, her father objected. The funeral was held the afternoon of her death at the home of relatives, some sixteen miles southeast of Springfield.

Prosecutor John A. Patterson declined to hold a preliminary examination; he thought the grand jury could handle the case. Theo was arrested on May 27 after the grand jury indicted him for 2nd degree murder; he pled not guilty. Theo’s $1500 bond was paid by a few prominent Springfield men, including T. B. Holland. Since he was underage, he could not be sent to prison; according to the Springfield Leader and Press, the charge would become a misdemeanor that would likely land Theo in the county jail for only a year.

Theo didn’t go to trial until February 1887. Dr. Tefft, witness for the state, testified about Julia’s injuries and her mental condition. He said the only thing he heard Julia say about the shooting was that it was “accidental,” which she repeated “a good many times” in front of everyone, including her family. By the time of her death on Thursday, Tefft stated that “she was more or less delirious…not all the time, but part of the time.

Another witness, an art teacher at Drury College, confirmed that Julia said the shooting was an accident. She also recounted that Theo had no contact with Julia other than asking if there was anything he could do to help.

There was much discussion at the trail about the condition of the gun and whether or not Theo knew it was loaded. Theo claimed that he did not; his younger brother Douglas had loaded it to hunt rabbits without Theo’s knowledge. Also, it had been taken to a gunsmith a few weeks prior to the shooting to have a new hammer installed. Theo and his brother complained that the gun wasn’t reliable; sometimes it would shoot, sometimes not. The gun was not repaired because the gunsmith couldn’t find a hammer that would fit.

The trial lasted four days. On Sunday, February 5th, Theodore Morrison was found guilty of manslaughter and fined $500.

After the trial, the Morrison family moved to Wichita, Kansas, where Nathan became the first president of Fairmont College (now Wichita State University). He died in 1907 and his wife in 1926.

Theo graduated from Marietta College in Ohio in 1902, then obtained a law degree from Northwestern University. Due to hearing loss, possibly caused by the scarlet fever, he gave up law and became a librarian at Fairmont College. In July 1906, Theodore married Belle McHenry at her home in Aberdeen Mississippi. They had one child, a son also named Theodore, born in 1910.

Theodore H. Morrison died in July 1912. A notice in the Springfield Republic reported that Theo’s death was caused “by an abcess (sic) on the brain, the result of an attack of scarlet fever in childhood.” There was no mention of his manslaughter trial.