In early February 1903, the Springfield Republican reported that McIntire had been given leave of absence. She vacationed in St. Louis and visited various rescue homes and institutions where she had often sent people from Springfield.[1] While she was gone, her monthly report, this time addressed to Mayor Melette, was published. Her work had not diminished; the need in Springfield continued to be overwhelming. No doubt she was exhausted and in need of a vacation.[2]

[1] Springfield Republican, February 1, 1903.

[2] Springfield Republican, February 3, 1903.

McIntire’s absence from Springfield did not prevent Mrs. Blood from publicly bickering with her. The February 4th headline read “Mrs. Blood Now Has a Baby Boy to Give Away.” The child belonged to a girl named Jones who Blood specifically said that she, not McIntire, had cared for. Blood also wanted it made clear that she had been given money to help the girl and she used it only for her benefit and no personal gain. There is no record of any response from McIntire, who may not have heard of the incident until much later.

The same day, Mayor Mellette vetoed a bill giving the police matron a salary on grounds that the city couldn’t afford it. The veto was sustained. [3]

[3] Springfield Republican, February 4, 1903.

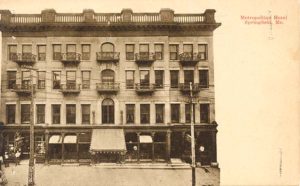

It was two months before McIntire returned from St. Louis and resumed her job as police matron.[4] She barely had time to unpack before a week-old baby boy was brought to Springfield from a Joplin Rescue Home and given to her to care for and find a home.[5]

[4] Springfield Republican, March 29, 1903.

[5] Springfield Republican, April 1, 1903.

The baby wars continued in August when a baby girl was left on Blood’s back porch. Since both women were known for their benevolence work, it’s not surprising that babies were left with them. Less than a year earlier, another baby girl had been left with Mrs. Blood; this one she kept and named Edwina. While Blood wanted to find the most recent baby a good home, McIntire, her police matron instincts kicking in, wanted to notify the police and have them find the mother. Blood, of course, objected to that plan, at which point McIntire accused her of enjoying having babies left on her doorstep. Blood denied the accusation, stating that she did not wish to start a “baby farm,” but would take care of any baby that God sent to her. Surprisingly, in spite of their public disagreements, while Mr. Blood was visiting family in Boston, McIntire was reportedly staying with her! [6]

[6] Springfield Republican, August 16, 1903.

Next up, Part IV – Scandal!