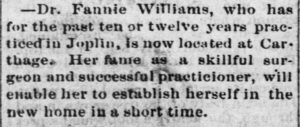

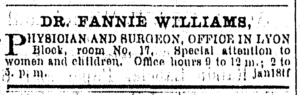

Galena, Kansas, Weekly Republican, October 10, 1885.

Dr. Fannie Williams is elusive. Though she was well known in the Joplin area during the 1870s and 1880s, little is known about her.

Fannie may have been born and raised in Kansas. (In 1885, her father and brother both lived in Kansas.)

She attended medical school at the University of Iowa and graduated in 1876.

By 1877, she was living in Joplin and treating patients. Although it was uncommon for female doctors to treat male patients, Fannie treated men, women, and children.

She was known occasionally as Mrs. Dr. Fannie E. Williams. In the 1880 Joplin census record, she was listed as a widow. Unfortunately, I have yet to determine her husbands name or find her marriage record.

In 1885, she was living and working in Carthage. “Her fame as a skillful surgeon and successful practitioner [enabled] her to establish herself in the new home in a short time.” She apparently had recently moved from Joplin to Carthage. Despite being a female in this era, she seemed to have little or no problem in being accepted as a qualified, competent doctor and was thus able to have a successful practice.

By 1886, Fannie was the superintendent of the Department of Health for the Carthage WCTU and regularly gave scientific lectures. At this time, the WCTU had a scientific education department, mainly focused on health, particularly the health benefits of abstaining from alcohol.

She still had ties to Kansas and even spoke in Garland as a state lecturer for the WCTU. She was invited to give a lecture there on July 3rd, 1886.

In 1886, the Missouri WCTU convention was held in Carthage and of course, Fannie was one of the speakers. She lectured the ladies on wearing too tight clothing, apparently a pet peeve of hers.

Throughout the month of June, 1887, Fannie spent her time in an Ozark court room with Cora Lee. She was with her throughout her trial for the murder of Sarah Graham. (For more about the murder, click here.) Fannie and Cora likely met through the WCTU.

In December 1887, Fannie left the Ozarks and moved to Riverside, California, apparently for her health. She continued to practice medicine and work with the WCTU, lecturing about health.

Riverside (California) Daily Press, January 18, 1888

Fannie was sick for much of the year in 1889. In October, the Riverside Daily Press reported that her health was much improved and she hoped to return to work soon. Unfortunately, her condition worsened and she died in early November.